Alternative Cartographies

Hope, desire, memory, nostalgia, oppression, exile, (be)longing are intrinsic aspects of spatiality. By considering a mixed body that is kneaded in its context through and through, we could perhaps create geographies that trace the paths to new virtual spaces of emancipation. The act of mapping would not seek to precisely reflect reality as we see it, but to allow encounters that can elicit new lines of flight. Such is the power of topological imaginations.

Geluidsmassage, geluidsinvasie: reflecties na concert van sun o))) op rewire, Den Haag, 7 April 2024

achter het steeds dichter wordend rookgordijn, doemen tien versterkers op. bij de deur worden oordoppen uitgedeeld. volle zaal, mensenstroom, het is duidelijk dat hier iets staat te gebeuren. sun o))) komt op en zo, daar, plots, de ruimte verandert in geluid.

(…)

Why Do We Meme?

Like most people of the Gen Z generation, I spent some of my formative years on the internet. Internet culture and memes have been a part of my life since I was around the age of twelve. It all started with an odd-looking frog and a socially awkward penguin, and somehow, I have now ended up with a somewhat extensive ‘personal’ collection of memes, consisting of ‘saved’ posts on Instagram and Twitter, and probably thousands of screenshotted images. When scrolling through these memes, I often wonder, besides smiling and giggling to myself, why am I doing this? Why are we doing this? By ‘this,’ I mean, both the saving of these images as well as repeatedly revisiting them, sometimes laughing out loud like I have not seen a meme at least ten times by now, and always feeling a weirdly deep sense of affective satisfaction.

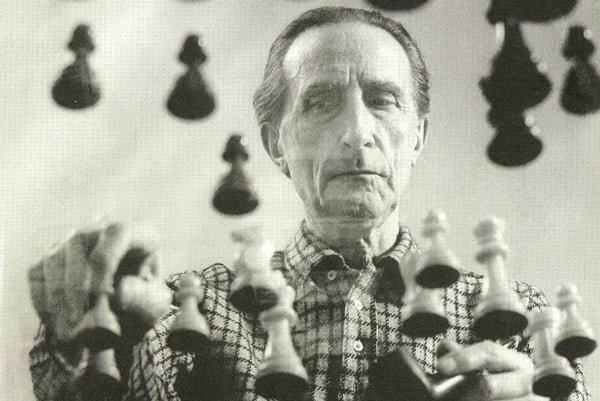

À Propos Use: Duchamp and the Canon

Marcel Duchamp’s notorious readymade Fountain (1917) has squeezed itself into art history and later proved to be of great importance to other art movements. The journey of its presence and absence offers valuable insights into the different means that can be employed to bestow a certain status upon an artwork. Despite current, lingering uncertainty regarding who originated the idea for Fountain, Duchamp’s manipulation of public perception and strategic use of reproduction underscore his reach.